The Library Of Mabel Mogaburu

As a sufferer of a sort of classificatory mania, from adolescence I took great care in cataloguing the books in my library.

By the fifth year of secondary school, I already possessed, for my age, a very reasonable number of books: almost six hundred volumes.

I had a rubber stamp with the following legend:

LIBRARY OF FERNANDO SORRENTINO

VOLUME Nº ______

REGISTERED ON: ______

As soon as a new book arrived, I stamped it, always in black ink, on its first page. I gave it its corresponding number, always in blue ink, and wrote its date of acquisition. Then, imitating the old National Library's catalogue, I entered its details on an index card which I filed in alphabetical order.

My sources of literary information were the editorial catalogues and the Pequeño Larousse Ilustrado. An example at random: in many collections from the various editors was Atala, René and The Adventures of the Last Abencerage. Motivated by such ubiquity and because the Larousse seemed to give Chateaubriand such great importance, I acquired the book in the Colección Austral edition from Espasa-Calpe. In spite of these precautions, those three stories turned out to be as unreadable as they were unmemorable.

In contrast to these failures, there were also complete successes. In the Robin Hood collection, I was captivated by David Copperfield and, in the Biblioteca Mundial Sopena, by Crime and Punishment.

Along the even-numbered side of Santa Fe Avenue, a short distance from Emilio Ravignani Street, was the half-hidden Muñoz bookshop. It was dark, deep, humid and mouldy, with creaking wooden planks. Its owner was a Spanish man about sixty years old, very serious, and somewhat haggard.

The only sales assistant was the person who used to serve me. He was young, bold and error-prone and had neither knowledge of the books he was asked about nor any idea of where they were located. His name was Horacio.

When I entered the premises that afternoon, Horacio was rummaging around some shelves looking for heaven-knows-what title. I managed to learn that a tall, thin girl had enquired about it. She was, in the meantime, browsing the wide table where the second hand books were on display.

From the depths of the shop, the owner's voice was heard:

'What are you looking for now, Horacio?'

The adverb now indicated a bad mood.

'I can't find Don Segundo Sombra, don Antonio. It is not on the Emecé shelves'.

'It is a Losada book, not Emecé; look on the shelves of the Contemporánea'.

Horacio changed the location of his search and, after a great deal of hunting, turned toward the girl and said:

'No, I am sorry; we have no Don Segundo left'.

The girl expressed disappointment, said she needed it for school and asked where she could find it.

Horacio, embarrassed in the face of such an insoluble problem, stared at her wide-eyed and raised his eyebrows.

Luckily, don Antonio had overheard:

'Around here', he answered, 'it is very hard. There are no good bookshops. You will have to go to the centre of town, to El Ateneo, or somewhere in Florida o Corrientes. Or perhaps near Cabildo and Juramento.'

The girl's face fell.

'Forgive me for barging in', I said to her. 'But if you promise to take care of it and return it to me, I can lend you Don Segundo Sombra.'

I felt as if I was blushing, as if I had been inconceivably audacious. At the same time, I felt annoyed with myself for having given in to an impulse that was contrary to how I really felt. I love my books and hate lending them.

I don't know what exactly the girl answered, but after some squeamishness she ended up accepting my offer.

'I have to read it immediately for school', she explained, as if to justify herself.

I learnt that she was in the third year in the women's college at Carranza Street. I suggested that she accompany me home and I would hand over the book. I gave her my full name, and she gave me hers. Her name was Mabel Mogaburu.

Before starting our journey, I accomplished what had taken me to the Muñoz bookshop. I bought The Murders in the Rue Morgue. I already had the Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque and, with much delight, decided to dive once again into the fiction of Edgar Allan Poe.

'I don't like him at all', Mabel said. 'He is gruesome and gimmicky, always with those stories of murders, of dead people, of coffins. Cadavers don't appeal to me.'

While we walked along Carranza toward Costa Rica Street, Mabel spoke enthusiastically and honestly about her interest in or, rather, passion for literature. Because of that, there was a deep affinity between us though, of course, she mentioned authors that differed from as well as matched my own literary loves. Although I was two years older than her, it seemed to me that Mabel had read considerably more books than me.

She was a brunette, taller and thinner than I had thought in the bookshop. She had a certain diffused elegance about her. The olive shade of her face seemed to hide some deeper paleness. The dark eyes were fixed straight on mine, and I found it hard to withstand the intensity of that steady stare.

We arrived at my door in Costa Rica Street.

'Wait for me on the pavement; I'll bring you the book right away.'

And I did find the book instantly as, for the sake of consistency, I had (and still have) my books grouped by collection. Thus, Don Segundo Sombra (Biblioteca Contemporánea, Editorial Losada) was placed between Kafka's The Metamorphosis and Chesterton's The Innocence of Father Brown.

Back in the street, I noticed, although I know nothing about clothes, that Mabel was dressed in a somewhat, shall we say, old-fashioned style, with a greyish blouse and black skirt.

'As you can see', I told her, 'this book looks brand new, as if I had just bought it a moment ago in don Antonio's bookshop. Please take care of it, put a cover on it, don't fold the pages as a marker and, most importantly, don't even think of writing even a comma on it.'

She took the book — such long and beautiful hands — with what I thought was a certain mocking respect. The volume, an impeccable orange colour, looked as if it had just left the press. She leafed through the pages for a while.

'But I see that you do write on your books', she said.

'Certainly, but I use a pencil, writing very carefully in very small handwriting; those are notes and useful observations to enrich my reading. Besides', I added, slightly irritated, 'the book belongs to me and I can do what I like with it'.

I immediately regretted my rudeness, as I saw Mabel was mortified.

'Well, if you don't trust me, I'd prefer not to borrow it.'

And she handed it back to me.

'No, not at all, just take care of it, I trust you.'

'Oh', she was looking at the first page, 'You have your books classified?'

And she read in loud voice, not jokingly:

'Library of Fernando Sorrentino. Volume number 232. Registered on: 23/04/1957.'

'That's right, I bought it when I was in the second year of secondary school. The teacher assigned it for our work in Spanish Lit classes.'

'I found the few short stories I've read by Güiraldes rather poor. That's why I never thought of getting Don Segundo.'

'I think you are going to like it, at least there are no coffins or cursed houses or people buried alive. When do you think you'll be returning it?'

'You'll have it back within a fortnight, as radiant' — she emphasised — 'as it is now. And to make you feel less worried, I am giving you my address and telephone number.'

'That's not necessary,' I said, out of politeness.

She took out a ballpoint pen and a school notebook from her purse and wrote something on the last page, then she tore it out and I accepted it. To be sure, I gave her my telephone number, too.

'Well, I am very grateful… I am going home now.'

She shook my hand (no kisses at that time as is the way now) and she walked toward the Bonpland corner.

I felt some discomfort. Had I made a mistake, lending my precious book to a complete stranger? Could the information she had given me be made-up?

The page from the notebook was squared; the ink, green. I searched the phonebook for the name Mogaburu. I sighed with relief: a MOGABURU, HONORIO was listed next to the address written by Mabel.

I placed a card between The Metamorphosis and The Innocence of Father Brown with the legend DON SEGUNDO SOMBRA, MISSING, LENT TO MABEL MOGABURU ON TUESDAY 7TH OF JUNE 1960. SHE PROMISED TO RETURN IT, AT THE LATEST, ON WEDNESDAY 22ND OF JUNE. Under it, I added her address and phone number.

Then, on the page of my agenda for the 22nd of June, I wrote: MABEL. ATTN! DON SEGUNDO.

That week and the next went by. I continued with my usual, mostly unappreciated, activities as a student in my last year of secondary school.

It was the afternoon of Thursday the 23rd. As often happens, even to this day, I had written a note in my agenda that I later forgot to read. Mabel had not called me to return the book or to ask me to extend the loan.

I dialled Honorio Mogaburu's number. At the other end, the bell rang ten times but nobody answered. I hung up but called again many times, at different times, with the same fruitless result.

This pattern was repeated on Friday afternoon.

Saturday morning, I went to Mabel's home, on Arévalo Street, between Guatemala and Paraguay.

Before ringing the bell, I watched the house from across the street. A typical Palermo Viejo construction, the door in the middle of the facade and a window on each side. I could see some light through one of them. Was Mabel in that room, engrossed in her reading…?

A tall, dark man opened the door. I imagined he must be Mabel's grandfather.

'What can I do for you…?

'I beg your pardon. Is this Mabel Mogaburu's home?'

'Yes, but she is not here right now. I am her father. What do you want her for? Is it something urgent?

'No, it's nothing urgent or very important. I had lent her a book and… well, I need it now for…' — I searched for a reason — 'a test I have on Monday.'

'Come in, please.'

Beyond the hallway, there was a small living room that appeared poor and old-fashioned to me. A certain unpleasant smell of stale tomato sauce mixed with insecticide floated in the air. On a small side table, I could see the newspaper La Prensa, and there was a copy of Mecánica Popular.

The man moved extremely slowly. He had a strong resemblance to Mabel, the same olive skin and hard stare.

'What book did you lend her?'

'Don Segundo Sombra.'

'Let's go to Mabel's room and see if we can find it'.

I felt a little ashamed for troubling this elderly man that seemed so down-on-his-luck and who lived in such sad house.

'Don't bother', I told him. 'I can return some other day when Mabel is here, there is no rush.'

'But didn't you say that you needed it for Monday…?'

He was right, so I chose not to say anything.

Mabel's bed was covered with an embroidered quilt with a faded shine.

He took me to a tiny bookcase with only three shelves.

'These are Mabel's books. See if you can find the one you want'.

I don't think there can have been one hundred books there. There were many from Editorial Tor among which I recognized, because I too had that edition from 1944, The Phantom of the Opera with its dreadful cover picture. And I spotted other common titles, always in rather old editions.

But Don Segundo wasn't there.

'I took you here so you wouldn't worry', said the man. 'But Mabel hasn't brought books to this library for many years. You can see that these are pretty old, right?'

'Yes, I was surprised not to see more recent books…'

'If you agree and have the time and the inclination', he fixed his eyes on me which made me lower mine, 'we can settle this matter right now. Let's look for your book in Mabel's library.'

He put on his glasses and shook a key ring.

'In my car, we'll be there in less than ten minutes.'

The car was a huge black DeSoto that I imagined was a '46 or '47 model. Inside, it smelled of stale air and mouldy tobacco.

Mogaburu went around the corner and entered Dorrego. We soon reached Lacroze, Corrientes, Guzmán and we turned onto the inner roads of the Chacarita cemetery.

We got out of the car and started walking along the cobbled paths. My blessed or cursed literary curiosity compelled me to follow him without question through an area filled with crypts. At one of them with the name MOGABURU on its facade, he pulled out a key and opened the black iron door.

'Come on,' he said, 'don't be afraid.'

Although I didn't want to, I obeyed him, at the same time resenting his allusion to my supposed fear. I entered the crypt and descended a small metal ladder. I saw two coffins.

'In this box,' the man pointed to the lower one, 'is María Rosa, my wife, who died the same day Frondizi was made president.'

He tapped the top several times with his knuckles.

'And this one belongs to my daughter, Mabel. She died, the poor thing, so young. She was barely fifteen when God took her away in May of 1945. Last month was fifteen years since her death. She would be 30 now.'

He leaned slightly over the coffin and smiled, as if recalling a fond memory.

'Death in all his unfairness couldn't keep her away from her great passion, literature. She continued restlessly reading book after book. Can you see? Here is Mabel's other library, more complete and up to date than the one at home.'

It was true - one wall of the crypt was covered almost floor to ceiling, I assume because of lack of space, by hundreds of books, most of them in a horizontal position and in double rows.

'She was very methodical, filling the shelves from top to bottom and left to right. Therefore, your book, being a recent loan, must be on the half full shelve on the right'.

A strange force lead me to that shelf, and there it was, my Don Segundo.

'In general', Mogaburu continued, 'not many people come to claim their borrowed books. I can see you love them very much.'

I had fixed my eyes on the first page of Don Segundo. A very large green X blotted out my stamp and my annotation. Under it, in the same ink and with the same careful writing in upper case letters there were three lines:

LIBRARY OF MABEL MOGABURU

VOLUME 5328

7TH OF JUNE OF 1960

'The bitch!' I thought, 'Even after I told her not to write even a comma.'

'Well, that's the way things go', the father was saying. 'Are you taking the book or leaving it as a donation to Mabel's library?'

Angrily and rather abruptly, I replied:

'Of course I am taking it with me, I'm not in the habit of giving away my books.'

'You are doing the right thing,' he replied while we climbed the ladder. 'Mabel will soon find another copy.'

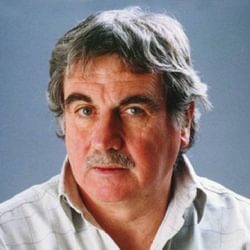

Argentine writer known for his engaging stories with satire and elements of the fantastical.